Two years ago I wrote this post about weird ETFs I own. Two years already?!? It does not feel it was so long ago…and in fact, I was sure I included an ETF…that I cancelled from my Bloomberg launchpad three days ago and now I cannot find it anymore, great.

OK. The ETF symbol is XYLD, the Global X Covered Call ETF. The ETF mimics the CBOE S&P 500 BuyWrite Index (BXM): in short, it is long the S&P 500 and selling one-month at-the-money call options on option expiration dates.

As explained in this paper (from where I unashamedly took this post title as well), the risk from this strategy comes from three sources: passive equity, short volatility and market timing.

- passive equity: the ETF invests in the S&P500, this part is easy to understand

- short volatility: the ETF sells options so it is short vol, again pretty intuitive

- market timing: this is the less intuitive part of the whole lot and it is generated as well by the sold option. The option pay-off depends on when the fund sells the option; if it does when the S&P500 is at the highest price of the month, the option will never expire in-the-money and the strategy will ‘never lose’. If it sells at the lowest price of the month, the option part of the strategy will always have negative returns [this is obviously just a theoretical point, no one knows if today will be the highest/lowest point compared to the next 30 days].

Now look at the Sharpe ratio of the S&P500 and BXM in below table:

This was the main reason why I invested in the ETF: BXM has a lower return than the S&P500 but has way lower volatility, which means each unit of risk is rewarded with higher returns.

First mistake: volatility is a poor proxy for risk

Volatility is widely used to indicate the risk of an investment mainly because it is easy to calculate and, in a lot of cases, the result is good enough. Are you familiar with the saying “the stock market takes the stairs up and the elevator down”? It means that down moves happen faster and changes are bigger than up moves. These are the main contributors to volatility, therefore its utility as a proxy for risk.

Now think about GME in 2020. The stock was very volatile. But if you were long GME, that volatility was only good for you, GME price exploded but upward, not downward.

So if volatility can happen up and down, what you would want is to eliminate downward volatility and keep the upward one. What BXM does is exactly the opposite. The investor has less volatility but the volatility that is missing is the good one!

Volatility Risk Premium

You forgo ‘good volatility’ but you get compensated for it because by selling options you get a premium. Is this exchange worth it? Before Xmas, Benn Eifert wrote a great thread that included the below pic.

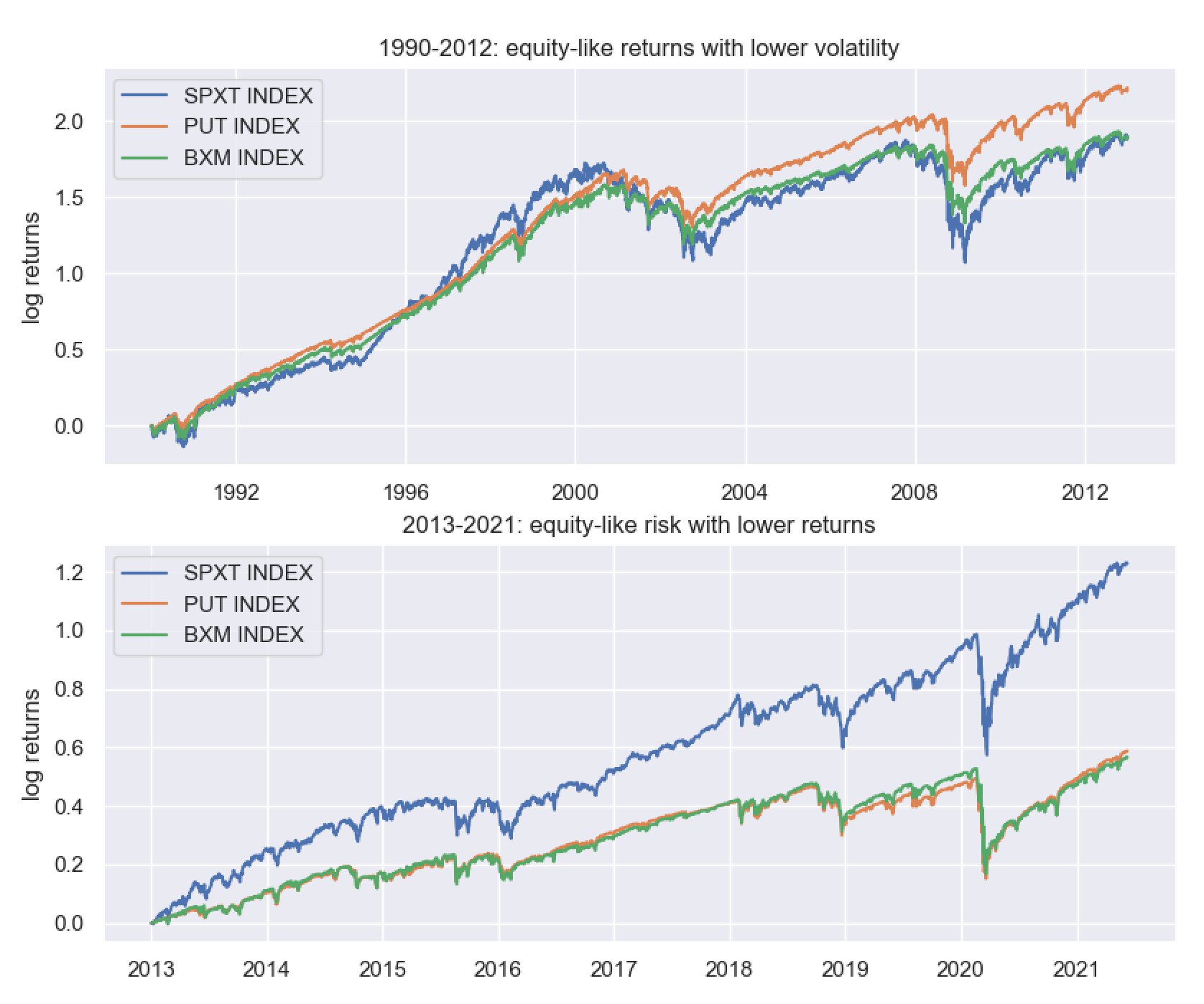

“BXM is long equity + short call, so the stand-alone performance of 1-month call selling is BXM minus SPXT (e.g. about flat 1990-2012, massively negative 2013-21)”.

[quick technical point: there is a reason why PUT and BXM have the same performance. Long equity plus short at the money calls is roughly the same thing as short at the money puts (by put-call parity). The modest difference in performance between BXM and PUT pre-2012 comes from idiosyncratic factors, mostly settlement].

There are two possible reasons why the performance of BXM-SPXT became negative after 2013:

- timing luck. As we said above, BXM sells options in a systematic fashion and the market knows when that strategy is selling. In Corey Hoffstein Q4 2021 commentary there is the following picture:

Implied volatility is basically the cost of an option (ceteris paribus) if you buy or the revenue if you sell. Corey shows puts but according to the put-call parity again, the same is valid for calls. Look how volatile that price is. A systematic strategy that sells options on the wrong day/moment (the market knows, remember) can receive way less than someone that pays attention to where the market is trading. Devil is in the details and there are a lot of details here.

- the specific trade became ‘crowded’. This is an aspect that is very difficult to see for non-pros. Benn mention it on Twitter and Paul Kim echoed him during this Animal Spirit podcast episode.

Second mistake: pay attention

If you want to invest in complicated stuff, you have to be sure you understand what you are doing (I only partially did, more on this later) and you have to check that the initial premises that made you pull the trigger continue to be valid.

In my particular case, the matter is even more complicated because I bought XYLD for the first time in 2016: my rationale was based on research made when this specific volatility premium was there but I bought when the opportunity was already taken away. My reference point was 2016, not the period 1990-2013.

The main reason why the volatility premium disappeared is as old as finance: someone found a profitable trade and took advantage of it until their ‘secret sauce’ attracted too many investors and the opportunity disappeared. Writing an option is like selling an insurance policy: the premium you get has to be high enough to compensate for the risk you are taking over. BXM is like an insurance company that has to sell protection but cannot set its own price, the protection is sold at a price set by the market. Sometimes that price does not justify the risk.

A second, deeper reason is probably that market ‘structure’ has changed. More actors trade options, institutions and retail investors.

This made markets susceptible not only to the old melt-downs but to melt-ups as well. The market might have learned how to take the elevator up (it is a phenomenon linked to “delta hedging” if you are interested in a deeper dive). If you sell calls, you should demand a higher premium for this reason; in reality, you get a lower premium because a lot of investors are loving the idea to be invested in equity with a volatility dampener (do you remember 2009? It left some scars)…wheatear they are conscious or not how much they are paying for that reduced volatility.

Buying/selling insurance is a probability game where we do not know the exact probability distribution. Today low premium, maybe combined with some good, old greed (the S&P500 had three incredible years in a row), might push enough investors away from selling calls that BXM will start to outperform again. A passive strategy is not being able to avoid crowded trades; an active strategy requires you to find the right manager, which sometimes is even more expensive. It is a complicated game.

Third mistake: the portfolio

I did not want to buy XYLD in isolation, I wanted to use the ETF in my portfolio. My third mistake, when I looked at table 6 at the beginning of this post, is that I did not pay attention to BXM Skew vs the S&P500. Negative skew means that big losses are more probable than big gains. As Benn puts it:

“As always, you need to think about the portfolio context and the opportunity cost of capital. As in the graph above, call write and put write strategies had roughly the same downside risk (down capture) as the underlying equity market, with much less positive performance in up markets. In a portfolio context, adding negative convexity strategies with low returns to the upside and high correlation to risk assets to the downside is generally not additive to portfolio performance”

When building a portfolio, two elements are very important: assets’ correlation and their convexity. You want uncorrelated assets, or even better negative correlation, and positive convexity/skew.

This is how I see it:

- if you have only one asset and you are not comfortable with S&P500

volatilityrisk, then XYLD might be a good substitute. XYLD offers some limited downside protection: if the market does not crash really fast, the premium on the sold call can soften the drawdown. This might be the difference between sticking to the plan and selling at the bottom. - if you have a 60/40 portfolio, bonds are already there to protect you from stocks downside. Switching from SPY to XYLD will generate more missed gains on the upside than relief on the downside. If 60/40 is too risky for you, it would be better to go 50/50 than XYLD instead of SPY.

- if you have only risky assets, XYLD is basically a non-diversifier.

Conclusion

Even if the call writing premium will go back to past, higher levels, XYLD might still not be a good fit in a portfolio. That said, volatility risk premium can still offer positive expected returns, uncorrelated with a certain degree to the equity risk premium. I just have to find a better product.

What I am reading now: